Jesus: Culture-Maker

Jesus in His Culture

Jesus of Nazareth, like every other man, was born into a culture. Throughout his life he continued to observe the customs, and to consume the culture, that he had received. Most of those who gathered around him and his message shared the same heritage and participated in the same traditions. To all the world, they seemed like a normal band of Palestinian Jews. His own disciples assumed throughout his public ministry that he would simply fulfill the prevailing messianic expectations of their society.

But even as Jesus observed the traditions and habits of his received culture, he subverted it. In subtle ways, he planted an adjusted worldview in the minds and hearts of his followers, and undermined many of the cherished assumptions, as well as the political powers, of his society. This subversion, though subtle, was significant and apparent enough that it led to his death. It was also effective enough that the result was a distinct culture, a new community, that over the course of a few hundred years, in the face of persecution and poverty, proceeded to permeate and transform the collection of cultures known as the Roman Empire.

Was this an accident? NT Wright believes it was not. He demonstrates in two significant volumes that Jesus knew exactly what he was doing; that his culture-creating work was not only effective, but intentional (The New Testament and the People of God, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1992; Jesus and the Victory of God, Minneapolis: Fortress Press, 1996). He builds his analysis primarily around four key roles of every worldview. These categories will provide us not only with an understanding of Jesus’ work as a culture maker, but also with the blueprint we need for our own work of cultural architecture.

ExcursUs: What is “culture,” anyway?

At this point, we need to pause for an overdue assignment: a definition of “culture” itself. Each of the authors we have considered would define it differently. For Niebuhr, culture is “the artificial, secondary environment which man superimposes on the natural,” consisting of “language, habits, ideas, beliefs, customs, social organization, inherited artifacts, technical processes, and values.” (Christ and Culture, 32) Newbigin defines it as “the sum total of ways of living developed by a group of human beings and handed on from generation to generation.” (Foolishness to the Greeks, 3) He likewise includes language, arts, technologies, law, social and political organization in the realm of culture. Andy Crouch, emphasizing the tangible aspects of culture, defines it as “what we make of the world.” Though he emphasizes the “product” aspect of culture, and specifically distinguishes it from “worldview,” he does acknowledge that it is “making sense” of the world as well as “making something” of it, concluding that culture is the “activity of making meaning.” (Culture Making, 23-24)

For the purposes of our conversation, I would propose the definition of Nieman and Rogers: “Culture is a human construct that includes both our patterns of meaning and our strategies for action.” (Preaching to Every Pew, 15) All of these authors, defining culture with their various emphases, include elements of both meaning and action — significance and product. This corresponds generally to what NT Wright calls “worldview.”

Though Wright emphasizes that worldviews have to do with the “presuppositional, pre-cognitive stage of a culture or society,” his description of worldview includes tangible aspects of culture, such as customs and artifacts. (NT and the People of God, 122) The distinctions are significant on a theoretical level, but for the purposes of our discussion, we will use the terms “culture” and “worldview” almost interchangeably, recognizing that “culture” is nuanced more toward tangible products, including language and social structures, while “worldview” is nuanced more toward meaning. The two cannot easily be separated, and they both figure significantly and jointly into our discussion of “cultural architecture”

What does a worldview do?

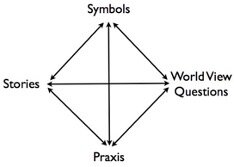

The four tasks of a worldview, in Wright’s analysis, include both meaning and practice. First, the worldview provides the “stories through which we see reality.” Second, it provides answers to four basic worldview questions: who are we, where are we, what is wrong, and what is the solution? Third, the worldview defines the symbols of a society—artifacts and/or events that represent cultural “boundary markers.” Observance or non-observance of these symbols would define whether or not a person is an insider or an outsider. Finally, a worldview includes praxis, or a people’s way of being in the world. (NT and the People of God, 122-125)

Every task of the worldview relates to every other. The horizontal line between “Stories” and “Questions” is the basic axis of meaning, while the vertical line between “Praxis” and “Symbols” defines the realm of practice, or action. But the Symbols derive their meaning from the Stories and the answers to the Worldview Questions. And Praxis is the living out of these in the life of the community.

Jesus and the Culture of 1st-Century Palestinian Judaism

Wright analyzes the culture in which Jesus taught in light of these four tasks. The stories that defined Israel’s view of the world told of a God who had rescued his people from slavery, and had placed them in the promised land, giving them the Torah as a definitive guide for living. The symbols that marked the boundaries of their society were the Temple, the Torah, the Land itself, and their racial identity as the people of God. These stories and symbols were fleshed out in a praxis that included Sabbath worship and festivals, study of the Torah, and obedience to the Law. If asked the four worldview questions, 1st-Century Jews would have answered something like this:

Who are we? We are Israel, the chosen people of God.

Where are we? We are in the Holy Land, promised to our fathers.

What’s the problem? Though we are physically out of exile, we are in exile still, because we are ruled by pagans, compromised Jews, and half-breeds.

What is the solution? We wait expectantly for a new kind of ruler, given by God, who will reestablish the true rule of God in the land.

Jesus and his followers shared this cultural heritage, but within a few years of Jesus’ ministry, a clear culture had immerged which was radically different. The story they told was the same story, with a different ending. God had acted finally and climactically in Jesus to fulfill his promises to Israel.

In praxis, they celebrated none of the Jewish festivals, worshipped on a Sunday instead of Saturday, practiced Baptism and the Lord’s Supper instead of animal sacrifices, adhered to a code of conduct that was not a distinctive mark of a chosen race, but the way of life of the people of God of all races. Instead of striving and looking for revolution or the establishment of an earthly rule, they launched a mission to proclaim a new heavenly kingdom.

Their symbolic world revolved around the cross, with Christ himself seen as the locus of God’s presence, completely substituting the Temple. Racial identity was supplanted symbolically by the church itself, as the people of God. The Torah was replaced by a new body of belief, a gospel to be proclaimed about the nature and activity of the true God.

Their answers to the four worldview questions reflected continuity with their past culture, but with a significantly different trajectory:

Who are we? A new group, yet not new, because we are the people for whom the God of Israel had always been preparing.

Where are we? In the world God has created, but which does not yet acknowledge him.

What is wrong? Paganism, persecution, heresy, and lust, which all need to be subjected to the rule of God.

What is the solution? Israel’s hope has been realized in Christ, victory had been initiated, and will be completed when the King returns to judge the world. (NT and the People of God, 359-370, 402-403)

How Jesus created a new culture

How did such a radical transformation take place? Jesus appeared on the cultural scene as a Jewish apocalyptic prophet, telling a story of God’s kingdom that seemed familiar, yet which subverted the prevailing telling of it, by redefining its terms and its expectations. He introduced, in the Sermon on the Mount among others, a praxis of the kingdom reflective of this new story. He undermined the symbols of 1st-Century Judaism (especially the temple) in a way that provoked such controversy that it ultimately led to his death, which in turn created one of the most powerful symbols of the new community (the cross). He offered new answers to the worldview questions:

Who are we? We are the true Israel, finally in the process of being redeemed by God.

Where are we? We are in a kingdom that is not limited to the Holy Land, but which embraces all of creation.

What is wrong? The ultimate enemy of God’s kingdom is not Rome, but Satan.

What is the solution? Jesus proclaimed that in his own life and ministry, the kingdom was being fulfilled. (Jesus and the Victory of God, 147-461)

Implications for preaching

This brief summary of hundreds of pages of analysis of the texts and background of the New Testament hardly does justice to Wright’s remarkable work. My purpose here, however, is to offer a broad picture of Jesus’ ministry as a paradigm for our approach as preachers to the cultural architecture of our communities. Wright’s framework gives us handles for understanding the cultural transformation that Jesus’ ministry achieved. It also provides categories for thinking about our own preaching ministries as we seek to nurture alternative communities that would assume creative, transformational postures toward the cultures in which they live.

Story, Worldview Answers, Symbols, and Praxis make up the essential structure of any culture, including the culture of a local church. While the preaching ministry of a church is not the only tool for culture building, it is the first and most visible, and a church’s culture is not likely to develop independently of the message it proclaims. From the earliest days of the church, the “ekklesia” of God’s people gathered around the proclamation of a culture-defining message. If we would in our preaching build a church culture that offers a distinct and viable alternative to the cultures of the world around us, we would do well to give careful and balanced attention to each of these four categories. They will serve us well both for our exegesis of prevailing culture and for the definition of the culture we wish to build.

In the next four posts, we will explore the cultural architecture of preaching in terms of these four categories: Story, Worldview Questions, Symbols, and Praxis.