The Sermon in Three Acts

Sermon Outline or Sermon Plot?

Years ago, Eugene Lowry wrote a little book entitled Doing Time in the Pulpit (Abingdon Press, 1985). In it he noted the irony of thinking of our sermons in terms of “structure” as if their subject matter is not temporal, but spatial. People live in time, come to church in time, listen to our sermons in time walk back into a time-oriented reality when the sermon is over. But for the 30 minutes in which they are actually receiving the message, we ask them to suspend their timely living and think spatially as we build a structure before them. When they leave, we hope they will manage to translate that spatial construct into real-time living.

Lowry suggested, and I agree, that we might better serve our hearers if we think of our sermon less in terms of a structure with an outline, and more as a story with a plot.

Five Narrative Events in Three Acts

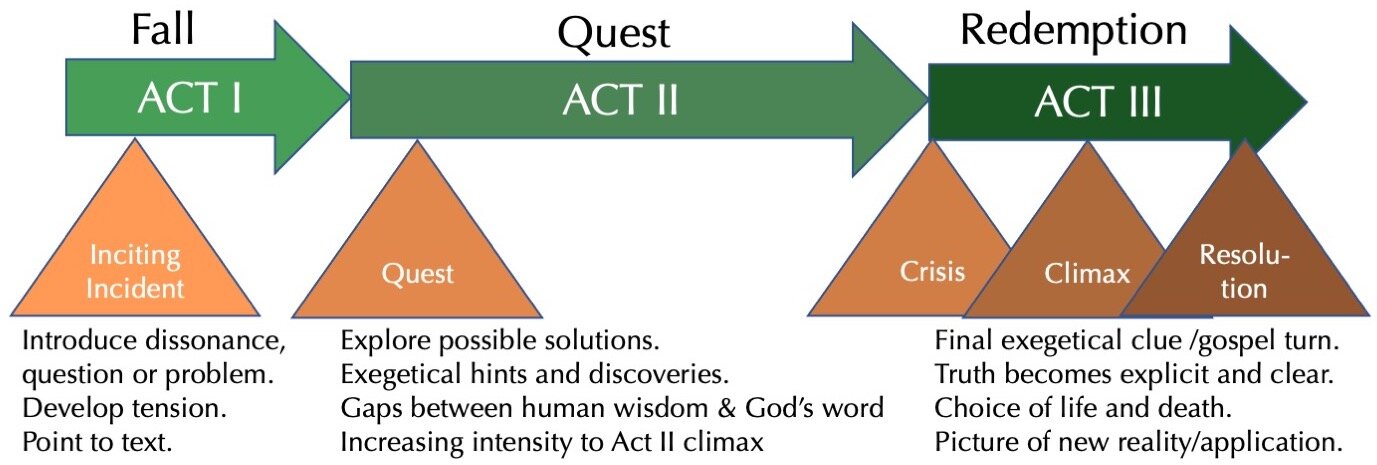

“Plot” is the sequence of events through which a story moves. Aristotle saw two fundamental movements common to all plots: the complication and the dénouement. (Poetics, XVIII) Contemporary fiction writers expand the list to five events. It is no coincidence that these correspond almost precisely to the five movements described by Lowry as the “homiletical plot.” (The Homiletical Plot: The Sermon as Narrative Art Form. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press, 2001, 27-87) They are time-honored and universal—prominent in all narrative genres and media, from simple storytelling, to literature, to the silver screen.

Film makers arrange these five movements into three acts. In Act I, once the setting and main characters are introduced, the equilibrium of their lives is somehow upset by an Inciting Incident, launching the tension of the story. After some development of this tension, Act I ends by launching the Quest, which continues through most of Act II. This is the longest stretch of the movie, consisting of multiple scenes, sequences, narrative gaps and reversals, as the characters attempt to resolve the problem created by the Inciting Incident. In Act III, the conflict comes to a head as the protagonist faces an ultimate choice with profound consequences. This Crisis gives way to a Climax in which a dramatic and irreversible change takes place, revealing the essential meaning of the story. In the final Resolution, the audience gets a brief picture of life on the other side.

Though storytellers give us endless variations on this basic sequence, this is the fundamental plot of every good story, from Little Red Riding Hood to the latest epic blockbuster. We can even see this plot in the greatest story of them all, the story of God.

The Plot of the Gospel

The Bible begins with a state of perfect equilibrium, the good creation of God. Everything is in order and as it should be, including the relationship of human beings with their creator, their position as his viceregents on the earth and their place in the garden he has prepared for them. Their rebellion against God is the Inciting Incident of Act I, putting in motion the tension and the sequence of events that will carry the story forward to its conclusion. A series of scenes develops the full gravity of the problem created by the fall – a loss of intimacy with one another and with God, an altered relationship with the natural world, family strife and societal corruption. Act I ends as human idolatry reaches critical mass in the city of Babel and humanity is scattered across the earth, fractured and divided by the confusion of languages.

The opening verses of Genesis 12 launch the quest, as God chooses Abram and makes promises to him of blessing, descendants, land and, most importantly, that through him all of the scattered families of the earth will be blessed. Act II continues through the rest of the Old Testament as these promises gradually, partially, haltingly find fulfillment. Barrenness gives way to fertility, slavery to freedom, wilderness wandering to a settled home in the land of promise, exile to restoration. God reveals himself to his people through mighty acts, miraculous provision, gifted leaders and anointed spokesmen. Through countless gaps and reversals, the story moves forward in search of the solution to the problem of Act I, the completion of the quest of Act II. At the end of the Old Testament there is a sense of anticipation, a conviction that the problem of sin will only be solved by an extraordinary provision of God.

Act III dawns quietly with a humble birth in a manger. The full significance of this event unfolds as the child becomes a man, demonstrating by his actions that he is both God and man, proclaiming a kingdom that is both rooted in the works of God in Israel’s past and pointing forward towards a surprising future. His death on a cross provides the Crisis of the narrative, and his resurrection is the Climax beyond which nothing can ever be the same. In this sequence the meaning of the entire story becomes clear. An extended Resolution portrays a new community gathered around these events, discerning and living their implications and anticipating a final restoration in a new creation. The tension is resolved, the promise is kept, the journey is complete.

I call these three acts “Fall, Quest, and Redemption.” They not only find expression in the gospel story, but also in the experience of every believer. The path towards faith begins with a sense of our brokenness, proceeds through a process of seeking, and culminates in the death to an old life and resurrection to a new one. This pattern continues in a Christian’s life through the ongoing process of sanctification as conviction leads through struggle towards transformation.

Preaching the Plot of the Gospel

If “story” is the shape of the gospel and of Christian conversion, experience and growth, why should it not be the shape of our preaching? In my own preaching ministry, and in my ministry of teaching preachers, I have settled on this as my preferred way of organizing the sermon. Here’s what it looks like:

Act I: Fall

An inciting incident pierces the normalcy of our lives, revealing our brokenness in relation to God, and creating some tension that must be resolved. We encounter a question we cannot answer, a sin we cannot overcome, a need we cannot meet, a longing we cannot satisfy, a problem we cannot solve. We explore briefly the dilemma before us, leading us to the realization that the problem is beyond us, that the answer will not be easy. The first act of the sermon leaves us with a question: How will this issue be resolved? How will God’s love meet us in our brokenness?

Act II: Quest

With growing intensity, we explore God’s quest to redeem and transform us, and the tension between our fallenness and His holiness. The wisdom of God’s Word leads us ever nearer to the answer we need. Biblical exposition reveals clues along the way, and a picture of God’s plan begins take shape. Even as we begin to grasp God’s purpose for us, however, we become aware once again that we cannot achieve his ideal. We are not capable of the life to which he calls us. The second act ends on a climax that brings us as close to a solution as humanly possible, but which falls short of final resolution. We longingly anticipate the breakthrough of the gospel, the infusion of grace.

Act III: Redemption

The final pieces of God’s solution to our brokenness fall into place. God’s answer to our need is to offer himself. At the center of the resolution is the cross and resurrection of Christ – the ultimate expression of Go doing for us that which we could never achieve. We are faced with a crisis that reframes our struggle in the form of an ultimate choice: There must be death for resurrection to take place. Will we die to sin, that we might live to God? The climax of the sermon reveals the truth that answers the question of Act I clearly and dramatically. The Gospel changes everything, leaving us with a mind-bending, life-altering understanding. The sermon ends with a resolution that paints the picture of new life on the other side of grace.

As we continue this series, we will look at each of these acts in more detail to give you very specific handles for developing a each part of a story-shaped sermon. But first, we need to define three crucial elements for your sermon that will make all the difference.